How Was Leonardo Da Vinci Influened by Greek Art

Abstract

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) can be called one of the earliest contributors to the history of anatomy and, past extension, the study of medicine. He may take even overshadowed Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), the so-chosen founder of human anatomy, if his works had been published within his lifetime. While some of the best illustrations of their time, with our modern knowledge of anatomy, it is articulate that many of da Vinci'due south depictions of human anatomy are inaccurate. However, he likewise fabricated significant discoveries in anatomy and remarkable predictions of facts he could not even so observe with the technology available to him. Additionally, da Vinci was largely influenced by Greek anatomists, as indicated from his ideas virtually anatomical construction. In this historical review, we describe da Vinci's history, influences, and discoveries in anatomical research and his depictions and errors with regards to the musculoskeletal organisation, cardiovascular system, nervous system, and other organs.

Introduction

The history of medicine and the history of the study of human being anatomy get paw in hand as about early on physicians were anatomists and vice versa. In fact, in antiquity, at that place was no articulate distinction betwixt these 2 roles. Although Flemish medico Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) is widely considered to be the founder of modern human anatomy, centuries later, the discovery of Leonardo da Vinci'due south (1452–1519) anatomical depictions and descriptions would plough this notion on its ear. Herrlinger has said anatomical illustration before Leonardo was archaic and believed at that place were examples in Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica that he had indeed seen at least some of the illustrations from da Vinci's notebooks [4]. da Vinci's papers were published between 1898 and 1916 as facsimile editions and so in a conservation try, in the early 1970s, all of his drawings, many with related notes, were arranged together and then published in 1979 [iv]. Temporally, da Vinci'due south notebooks were created well before (15th versus sixteenth century) Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica, which was published in 1543. da Vinci'due south anatomical drawings and notes were compiled during the early 1500s on xviii double-sided pages [ii]. On these pages, he depicted 240 drawings and his notes on these pages were well over 13,000 words [2, 4].

Vesalius'south work is then highly regarded that the history of the report of anatomy is often categorized into pre-Vesalian and post-Vesalian periods, i.e., before and after the publication of De humani corporis fabrica. Parenthetically, Clayton and Philo have written that if da Vinci's notebooks had been published during his lifetime or before Vesalius's 1543 work that today nosotros would about likely refer to pre-Leonardian and post-Leonardian periods for the history of the written report of homo anatomy [two]. However, through close inspection of da Vinci's notebooks, i can come across that while his anatomical depictions where accurate in many respects, they were often misdirected and bluntly wrong [1]. For case, Galen's teachings such as the notion that the nasolacrimal duct functions to drain tears from the eye, veins, and arteries is found in his writings. In this paper, the hypothesis is that the outset century teachings of Claudius Galen (129 Ad–c.200 Advertising) and his followers continued to influence da Vinci and the style he described and drew the man anatomy in the Middle Ages over a millennium afterwards [4].

Although da Vinci's anatomical illustrations were well before their fourth dimension, some have pointed out that in the reality of medical illustrations and in item in regard to homo form, there was extremely little competition to his drawings [ane, 4]. The anatomical drawings bachelor during da Vinci's life were artless and oft not based on reality [nine]. Older and often incorrect texts with Galenic influences that would accept been freely bachelor in da Vinci'south day, every bit such was "widely read and circulated in the center ages", and which could take easily influenced his concepts of human beefcake included Mondino de' Luzzi's (1275–1326) Anathomia published in Bologna in 1482 and Avicenna'southward (980–1037 Advert) Canon [10]. In fact, nosotros know that da Vinci was familiar with Mondino equally in his collection of notebooks, he referred to the works of Mondino with reference to his descriptions of the extensors muscles of the toes [3]. da Vinci would too have been familiar with other authoritative anatomical works of the era. For example, Alessandro Benedetti (1450?–1512), a Greek scholar and medical professor at the Universities of Bologna and Padua, had published in 1497 an anatomical guide consisting of 5 books (Anatomice). These tomes dealt with the structure and dissection of the man body merely lacked originality [seven]. From da Vinci'southward notebooks, one sees that he was familiar with Albertus Magnus' (circa 1200–1280) piece of work on beefcake, De Animalibus. Other extant anatomical authors that da Vinci would take known of included Achillini, Zerbi, and Benedetti the latter ii of whom he mentions in his notes [11]. It is also known that da Vinci owned the following books that included anatomical descriptions: Johannes de Ketham's Fasciculus Medicinae, Guy de Chauliac'southward Cyrurgia, and Bartolomeo Montagnana'southward Tractatus de urinarum judiciis. Lastly, equally the original Greek texts from Galen were not extant, the only known manual of his work was via Arabic translations. Therefore, it is interesting that one of his notes stated, "take Avicenna translated" and that Avicenna, a Persian scholar, would have been well versed in Galenic medicine in his mean solar day [11]. Although non confirmed by others, O'Malley and Saunders stated that late in da Vinci's life, he caused Galen's book (mostly Standard arabic translations) De usu partium [vii]. Park besides seems to think this influence probable, stating that "Fourteenth and fifteenth century medical writers relied for the almost role on the relatively brief anatomical passages in Avicenna's Canon and on abbreviations and adaptations of the Galenic texts" [8]. These authors and so boldly stated that from this point forward, da Vinci was essentially a Galenist. These authors also land that da Vinci came upon this re-create of Galen'south work around 1510. However, the majority of da Vinci's anatomical drawings were made between 1505 and 1510 [2,three,4, vii, 9].

Scholars of aboriginal medical catechism were largely influenced by da Vinci's works, peculiarly he had access to many human cadavers for further investigation and could have overturned these before incorrect notions with simple dissections. Todd stated in his book devoted to da Vinci's neuroanatomical understanding:

"Information technology is never like shooting fish in a barrel to shake off the spell-binding enchantment of tradition and Leonardo'south expressed intention to read from nature was no exception. Gross errors of received stance are repeatedly manifested in his drawings, and obvious mental blocks imposed past a sure subservience to authority continually undermine his theoretical precepts. He was never able to erase these barriers to codify any valid general principles of neurological role" [11].

Herein, the link between errors constitute in da Vinci's writings and the writings of Galen will be investigated. Reasons for why the inclusion of such errors into da Vinci'southward notebooks occurred considering he had many human being cadavers at his disposal and would have been able to see the "truth" with his own optics via cadaveric dissection volition also be explored. As Todd eloquently stated,

"Although Leonardo never successfully unraveled himself from the bonds of traditional say-so he did loosen them as his enquiring knife disclosed the true form of things to the critical eye. In this investigation he tried to discard the confused aboriginal texts to read from the book of nature" [11].

The importance of Galen

To better understand the temper of the day, it is important to know that Galen and his teachings were considered infallible over nigh of the pre-Vesalian catamenia. Galen was the well-nigh important dr. of the Roman Age and came to Rome after grooming in Alexandria [10]. About of the human beefcake taught by Galen was derived from his dissections of the pig and as he said, "the fauna near similar to human" and monkeys and apes [10]. Galen was the reference betoken for medicine throughout the Arab and Christian worlds with the Arabs being directly responsible for transmitting his words via Arabic translations once the original Greek texts were no longer extant. Galen'southward teachings would come to Europe primarily via Islamic Spain [x]. Cordoba was the home of many of import Islamic scholars who propagated Galen'southward philosophy and agreement of medicine and in item, knowledge of the human being anatomy. Such scholars included Averroes, which is the Latinized form of Ibn Rushd who lived from 1126 to 1198 [ten]. Averroes was a defender of early Greek teachings such as those of Aristotle and Galen. Later the autumn of Muslim Spain, many Islamic scholars spread throughout Europe and peculiarly to French republic and Italia. Here, the teachings of Galen through the translations and educational activity of these Islamic scholars continued to be accepted as gospel and spread throughout the European world. Scholars that influenced da Vinci derived from this lineage from Galen to Islamic Spain and then to Europe and specifically Italy included Mondino. Mondino trained at Montepellier and so in Bolgna [ten].

Da Vinci's anatomical errors

Conspicuously, da Vinci made significant discoveries in anatomy. Not only did he describe sure anatomical structures for the kickoff fourth dimension, but he also recognized the true curvature of the spinal column and the true position of the fetus in utero [ane, 9]. However, i has to ask why one if non the best collection of anatomical drawings of the European Middle Ages from a man well ahead of his time and who had accurate sources of research, i.e., man cadavers would illustrate anatomical structures such as those mentioned before in an inaccurate way and in a manner that oftentimes, stemmed from the descriptions of these structures centuries earlier and as far back equally Galen. Could dedication to Galenic thought still exist in play for da Vinci's time? We know that although Vesalius, a century later, put together a marvelous and often considered new standard in the field of beefcake that some of his depictions still propagated Galenic thought [9]. Nonetheless, ostensibly, Vesalius dissected fewer cadavers and thus had less opportunity to correct all incorrect and blowsy thoughts and erroneous descriptions about human morphology. Additionally, why were some Galenic anatomical teachings overturned by da Vinci while others connected to be embraced? These questions will be addressed by examining both main and secondary sources on the topic of da Vinci and his knowledge of anatomy as presented in his notebooks [9].

Clearly, there are examples in the writings and drawings of da Vinci that illustrate propagation of Galenic teachings. Although these were still the accustomed teachings of the day, they were probably reinforced past da Vinci'south mentor, Marcantonio della Tore. Della Tore is well known as being "1 of the first to begin to illustrate matters of medicine by the teachings of Galen and to throw true light on beefcake" [two]. This theory of Galenic involvement is further supported by various examples in the writings of da Vinci's notebook and volition be discussed subsequently [ii].

Todd captured his thoughts on Galenic influence of da Vinci by stating:

"We see Leonardo at his worst in his pretentious early efforts to give visual reality to ancient dominance on the subjects of generation or the situs of the senso commune. Nosotros squirm with his tortured quest to discover the true optics of vision under the mirage of preconceived notions that the prototype had to imprint on the optic nerve in an upright position. We are appalled when vivid discoveries are marred by slavish repetition of Galen's errors in the same drawings, or by completely erroneous interpretation of observed facts as when he fancies lateral auxiliaries of the spinal cord in the vertebral canals" [11].

As mentioned earlier, da Vinci rendered many anatomical structures incorrectly. The following subsections hash out specific anatomical errors as described and fatigued by da Vinci using a systems approach.

Musculoskeletal system

Regarding the skeletal system, da Vinci'due south depictions of the spine were often rudimentary and inaccurate [1]. He envisioned the vertebrae to be of uniform shape [1]. Still, his depictions of the spine improved over time, guided by further autopsy [1]. He even used his knowledge of physics to predict the placement of muscles and fretfulness necessary for realistic movement [1]. Regarding the muscular organization, da Vinci believed that the diaphragm and muscles of the abdominal wall were the structures involved in generating forces that then controlled motility of the gut [ii]. Additionally, his drawings of many of the facial muscles were ofttimes wrong [2].

Cardiovascular system

For the cardiovascular organization, the aortic arch is often not shown, the misconception of a rete mirabile in humans as taught by Galen is depicted, the correct testicular vein originates as well loftier from the inferior vena cava, and the centre is shown every bit having moderator bands on left and right sides. Interestingly, the only anatomical construction named after da Vinci is the normal moderator band of the right ventricle [2]. He described four umbilical arteries when there are only 2 [vii]. O'Malley and Saunders describe da Vinci'south understanding of blood flow equally a flux and reflux miracle as simply a "modification of Galenical theory" [7].

On one of da Vinci's drawings showing the vascular tree of the human torso, he labels ane system the "Spiritual parts" based on the Galenic venous organisation and "Vital spirits" for the arterial arrangement and based on the same teachings. On one pic of the heart, he uses Galen'due south comparison of the liver and vessels to a plant with the seed of Galen corresponding to the roots to the inferior vena cava and the branches below the hepatic veins and the stem to the upper portion and the inferior vena cava and its branches toward the heart was similar a constitute's fruit, an bagginess to the venous tree; however, in his notes made merely below this anatomical drawing, he takes on the position of Aristotle'due south teachings on this subject and says,

"the plant never arises from the branches for the establish showtime exists before he branches and the heart exist earlier the veins. The centre is the seed which engenders the tree of the veins these veins that have the roots in the dung, that is, the mesenteric veins which keep to deposit the caused blood in the liver form which the upper hepatic veins of the liver receive nourishment" [vii].

Nervous system

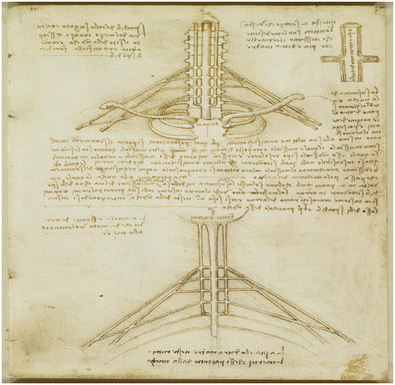

For the nervous system, the brachial plexus is shown on some drawings as having no first thoracic spinal nerve contribution, which usually contributes to its formation (Fig. 1) although this tin can be an uncommon anatomical variation in human anatomy.

da Vinci's sketch of the brachial plexus. Note that the brachial plexus is formed past only C5 to C8 and that there is no T1 contribution

O'Malley and Saunders believed that da Vinci's observations of the fretfulness of the extremities were all based on his dissections of monkeys where he so "distorted to fit the contours of man." The ventricles of the encephalon, which he primarily studied in oxen by injecting them with molten wax, and the cranial nerves as they emerge from the inferior surface of the skull base of operations were inaccurately fatigued and frankly, wrong [11]. Based on da Vinci's experiments on frogs, he believed that the middle of life was located in the spinal cord [7, 11].

Organs

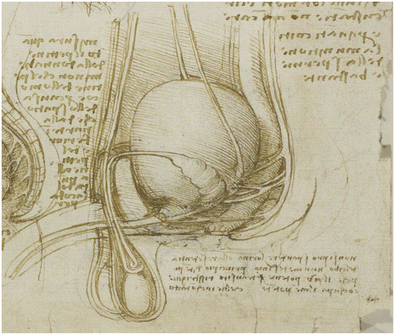

For organs, the spleen is shown as receiving an artery from the liver, the outer lung cavity described as containing air, which was a traditional teaching of Galen, the seminal vesicle is shown too laterally placed and the penis is illustrated and described as containing two passages, i for creature spirits and one for the emission of urine [11]. Interestingly, da Vinci believed as was common in his twenty-four hours that semen was produced past the spinal cord (Fig. 2) [11].

da Vinci'southward drawing of the male pelvic organs. Annotation the odd shape and size of the rectum backside the enlarged urinary bladder. The seminal vesicle is misplaced, and the spinal cord extends into the penis as da Vinci believed that semen arose from the spinal cord and was and so transmitted through the penis [eleven]

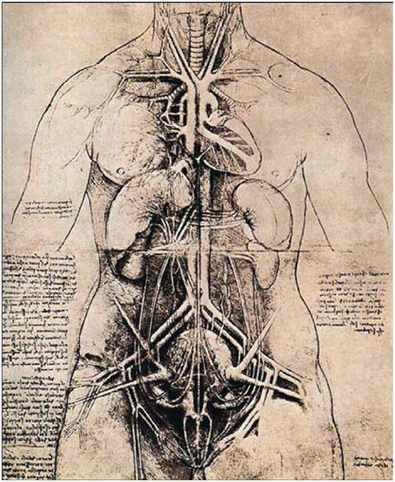

His lack of appreciation of peristalsis in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract was evident too in his clarification of the ureters and of the flow of urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. He viewed the ureter as a elementary tube through which fluids flowed as a result of gravity and even demonstrated in a series of diagrams the furnishings of various bodily positions on the flow of urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder [7]. In his descriptions and illustrations of the liver, he incorrectly demonstrated it equally having five lobes as Galen had taught. O'Malley and Saunders believed da Vinci was most erroneous anatomical descriptions were those of the male and female reproductive organs (Fig. 3) [vii]. They sum up these descriptions by saying these were "treated with a curious mixture of fact and fancy."

da Vinci's cartoon of organs of the female body. Note the abnormal uterus and its odd extensions. This representation is more than in line with what would be found in a female moo-cow [seven]

Vascari (1568) wrote on the life and works of da Vinci [2]. In the book, Vascari suggests that da Vinci was nigh probable influenced past Galenic teaching via his supposed collaborations (1510–1511) with Marcantonio della Torre at the University of Pavia [ii]. della Torre was a leading figure in his day for reviving Galenic teachings. Vascari notes that della Torre would have had admission to Arabic translations or Latin translations of the Arabic of the extant writings of Galen and every bit a professor, nearly likely would have influenced those under his mentorship such as da Vinci [2]. All the same, every bit da Vinci rarely referenced anyone in his writings, this direct connectedness is difficult to confirm [2]. Moreover, many of da Vinci's anatomical descriptions and illustrations were not made in Galenic anatomical tradition [2, 9].

Some might point to a poor ability to dissect equally leading to some of da Vinci'south "mistakes." Notwithstanding, the tremendous accurateness of most of his anatomical drawings and the details that only a thorough dissection of the human body would avail make this unlikely [ane]. Additionally, a diary entry on 10 October 1517 past Antonio de Beatis, a secretary for Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona, mentions how da Vinci's peers felt about his works.

"This gentleman has written in corking detail on anatomy, with illustration of the members, muscles, nerves, veins, joints, intestines, and of whatever else tin be discussed in the bodies of men and women, in a manner that has never however been done by anyone else. All this we have seen with our own eyes; and he said that he had dissected more than thirty bodies" [ii].

Additionally, da Vinci also dissected animals and depicted these in his notebooks. Illustrations of various animals include those of dogs, oxen, and cows [2]. As Galen only dissected animals and extrapolated these findings to humans, da Vinci might take washed the same. It is known that he often tried to make his findings in beefcake fit with the accepted understanding of the physiology of his day [1, two]. For example, when trying to elucidate the menstruation of blood to and from the centre (not fully understood until William Harvey'due south publication De motu cordis published in 1628), he realized that the left side of the heart pumped blood into the arteries of the body and that the valves on this side prohibited back menses during contraction [two]. However, he never expanded this understanding to include the right side of the heart and its function in receiving venous blood from the trunk and pumping it to the lungs and that this blood so returned to the left side of the heart to be circulated [two]. What he did do was deduce that blood must intermix between the arteries and veins so that at that place was not overfilling of i over the other [two]. This deduction required that these vessels interconnect at their very ends [2]. This deductive reasoning on the part of da Vinci might have been one reason for some of his inaccurate drawings of human anatomy, i.eastward., not seen with his ain eyes during autopsy and deduced as being the aforementioned or at to the lowest degree similar to what he had seen in his anatomical dissections of various animals [ii].

With regard to da Vinci beingness influenced by earlier anatomical knowledge, especially Galenic, Todd stated,

"Appropriately, it was hardly a carta rasa on which Leonardo recorded his anatomical findings; yet, the dubious quality of his anatomical inheritance was inordinately negative as a base of inspiration. However, the examiner volition notice petty originality in whatsoever of the anatomical illustration available to Leonardo aside from the topographical representations of the homo figure by his artistic peers. All medical analogy was characterized past a servile adherence to tradition scarcely improved past centuries of pale imitation" [11].

da Vinci began his study of the human being body from the viewpoint of an artist and not from the vantage point of a doc. This for an artist was necessary non just to visualize the human form just as well to understand its more deeply located structures and so that that the surface and underlying substance might be more than vividly depicted. In other words, to all-time capture the surface of his figures, understanding what contributes to this topography would exist important. da Vinci's anatomical drawings were in the tradition that began with the Italian painter Giotto (1267–1337) which displaced conventionalism and aimed at a more natural and realistic representation and thus made Giotto an early effigy of the Renaissance [eleven]. Only to create such magnificent anatomical drawings, demanded not only the skill to sketch accurately, merely also the unique ability of meticulous dissection and representation of the structures that were displayed. This artistic influence "flowed in the other direction as well. Artistic renderings assumed more space in anatomical texts and their quality profoundly improved as printing techniques became more than sophisticated" [5, 9, 11].

Soon, da Vinci's enthusiasm for dissection led him to the study of beefcake as a bailiwick in its ain right. He was considered a polymath of the Renaissance and is known to take studied botany, mathematics, geology, astronomy, philosophy, and beefcake both animal and man. His knowledge of human anatomy was known in his day. For example, ii years before his death, da Vinci was visited by Cardinal Luigi d'Aragon who stated,

"This gentleman has written of beefcake with such detail showing by illustrations the limbs, muscles, nerves, veins, ligaments, intestines, and whatsoever else there is to talk over in the bodies of men and women, in a mode that has never still been done by anyone else. All this nosotros take seen with our own eyes; and he said that he had dissected more thirty bodies both of men and women of all ages" [nine].

da Vinci recorded in his drawings precisely what he had observed and attempted to combine structure with role. His dissections were carried out in the infirmary of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence and after in Santo Spiritu Infirmary in Rome [nine]. On the topic of anatomical knowledge through human autopsy, da Vinci stated,

"… while in order to obtain an exact and complete noesis of these I accept dissected more than 10 human bodies … And as i single torso did not suffice for so long a time, it was necessary to proceed by stages with and so many bodies as would return my knowledge consummate; and this I repeated twice over in order to discover the differences. But though possessed of an involvement in the subject area, you may perhaps be deterred by natural repugnance, or if this does non restrain you then perhaps past the fearfulness of passing the night hours in the company of these corpses quartered and flayed, and horrible to behold, and if this does not deter you then perhaps you may lack the skill in drawing essential for such representation…Concerning which things, whether or not they have all been found in me, the one hundred and 20 books which I take composed will requite their verdict aye or no. In these I have not been hindered either past avarice or negligence, but just by desire of time" [6].

These words of da Vinci point that his anatomical investigations were calculated and deliberate. It is not evident from these comments that he tried to "cut corners" with his dissections only rather sought the truth. However, as he indicates in the last sentence of the excerpt above, time ("past only by want of fourth dimension") could have been a factor and in a day and historic period where modern features that inhibit human decay such as embalming fluids and refrigeration were not available, maybe fourth dimension was a significant and limiting factor and da Vinci may have only "filled in the gaps" with ideas or teachings that were Galenic. Based on his comments above, it is not clear at all that there was any direct pressure level from established anatomical teaching, i.e., Galenic that guided his descriptions and renditions then the human anatomical knowledge of his twenty-four hours could accept knitted together his straight anatomical findings when certain areas or features were not observed past him direct. This notion is supported past examples where he directly contradicted Galenic thought. One such example is that da Vinci opposed Galen's view that the liver is the source of the vena cava. Another example of how da Vinci did not accept everything known from antiquity related to anatomical principles was that he argued that Aristotle'south view that the origin of the vena cava was the heart was incorrect.

From da Vinci'southward quote higher up, it is clear that information technology was written during the earlier part of his life because of the prior reference to having dissected 30 man bodies 2 years before his decease [half dozen]. From the annotations in his notebooks, one learns that he had planned on writing a book devoted to anatomy [6]. The big number of anatomical drawings and extensive writings in his notebooks would have probably been included in such a text. At da Vinci's death on 2 May 1519, he bequeathed all his manuscripts and drawings to his beloved disciple, Francesco Di Melzi, who kept them secured for nigh 50 years [6]. Post-obit the death of Melzi in 1570, the manuscripts were passed on to his nephew Orazio [six].

Unlike his contemporaries, it was da Vinci alone who pursued the study of the human body with such thoroughness that he quickly transcended the needs of the artist and drifted into the scientific pursuit of anatomy for its ain terminate. His scientific rectitude was one of the beginning to bring Galenic anatomical teachings to the light. The anatomically incorrect drawings and descriptions occasionally found in his notebooks include articulate examples of beefcake that was counter current to Galenic teachings so that ane cannot conclude that da Vinci was consciously influenced by these showtime-century ideas. However, with limited time to dissect human cadavers and having ostensibly only dissected effectually 30 bodies, it is plausible that da Vinci simply and subconsciously substituted the prevailing Galenic thought, e.g., five lobes of the liver, the presence of a rete mirabile in humans, and the notion of an outer lung cavity described as containing air, into gaps in his dissection knowledge of the anatomy of the man trunk. The lack of mod techniques e.g., refrigeration for extending the longevity of cadaveric dissection very likely contributed to such anatomical substitutions. Therefore, a direct influence of Galenic teachings on da Vinci'south anatomical work is not supported by the available bear witness and known historical facts.

References

-

Bowen K, Gonzales J, Iwanaga J, Fisahn C, Loukas 1000, Oskouian RJ (2017) Leonardo da Vinci (1452-159) and his depictions of the homo spine. Childs Nerv Syst. doi:10.1007/s00381-017-3354-9

-

Clayton M, Philo R (2012) Leonardo da Vinci anatomist. Royal Collection Publications, London

-

Elmer P, Grell P (2004) Health, disease, and society in Europe, 1500–1800. Manchester University Printing, London

-

Herrlinger R (1970) History of medical illustration from antiquity to 1600. Heinz Moos Verlagsgesellschaft & Co., Munchen

-

Lindemann Thousand (2010) Medicine and society in early modern Europe. Cambridge Academy Publishing, Cambridge

-

MacCurdy Eastward (1939) The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Konecky & Konecky, One-time Saybrook

-

O'Malley CD, Saunders CM (2003) Leonardo da Vinci on the human body. Gramercy Books, New York

-

Park K (2006) Secrets of women: gender, generation, and the origins of human dissection. Zone Books, New York

-

Persaud V, Loukas Chiliad, Tubbs RS (2015) A history of human anatomy, 2nd edn. Charles Tuttle Publishing, North Clarenden

-

Taglialagamba S (2010) Leonardo & anatomy. CB Publishers, Rome

-

Todd EM (1983) The neuroanatomy of Leonardo da Vinci. Kapra Press, Santa Barbara

Conflict of involvement

The authors declare that they take no conflicts of interest.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Near this commodity

Cite this article

Tubbs, R.I., Gonzales, J., Iwanaga, J. et al. The influence of ancient Greek thought on fifteenth century anatomy: Galenic influence and Leonardo da Vinci. Childs Nerv Syst 34, 1095–1101 (2018). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s00381-017-3462-half dozen

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3462-6

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00381-017-3462-6

0 Response to "How Was Leonardo Da Vinci Influened by Greek Art"

Post a Comment